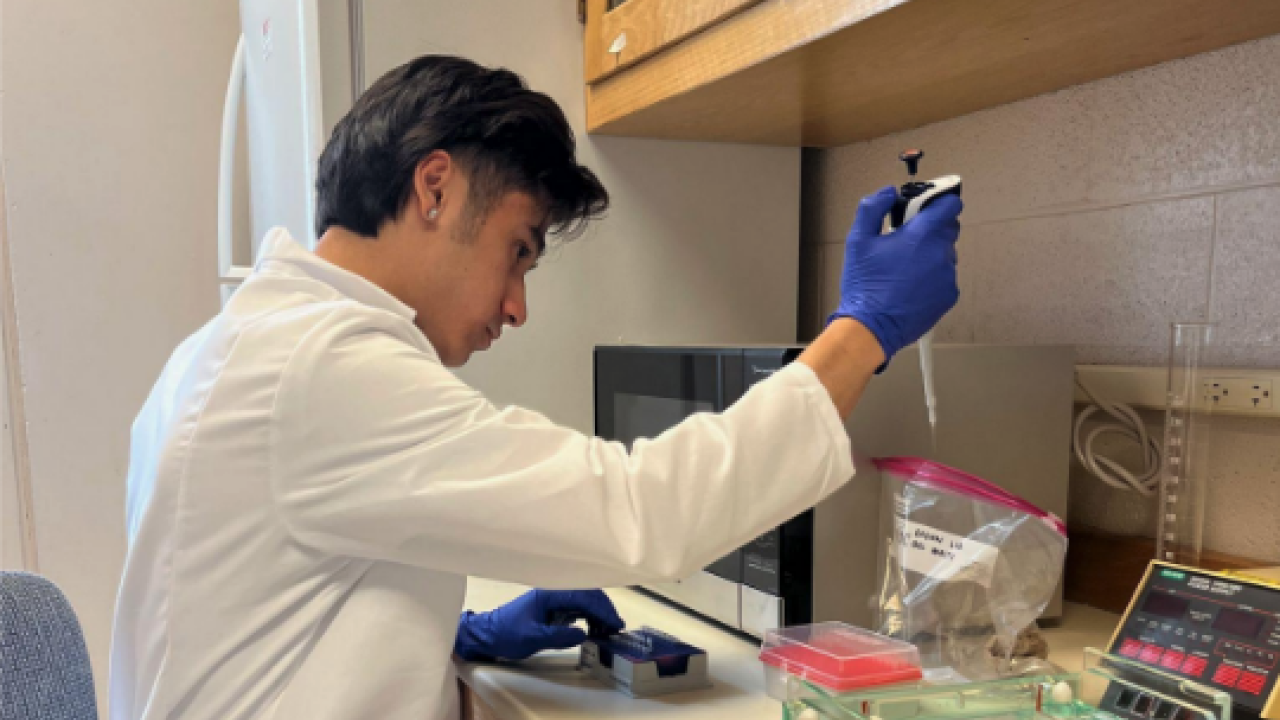

By Patrick PhengsyPatrick Phengsy is a fourth-year undergraduate student who just completed his Associate's Degree in Natural Sciences at the SRJC. He will be transferring to UC Santa Barbara for the upcoming Fall 2023 quarter, where he aims to complete his Bachelor’s Degree in Biology and pursue a career in medicine. This summer, I had the fantastic opportunity to work at the Bodega Marine Lab in partnership with the SRJC under Katie Erickson. My work this summer was mainly focused on further addressing the genotype distribution and demography of Zostera sp., otherwise known as Eelgrass, within Tomales Bay. All analyses were conducted in the laboratory setting, specifically in the Brown Lab, which was led by the excellent PI, Dr. Anya Brown. Throughout my experience, we implemented a variety of laboratory techniques and protocols, such as pipetting various volumes, DNA extractions, PCR amplification, and Gel Electrophoresis. Previously research had been conducted and published on the same topic I aimed to explore, where the investigators successfully analyzed the genetic distribution of Eelgrass within Tomales Bay. Although their data was relevant and made a substantial contribution to local marine science, the study consisted of specimens collected off specifically the east side of Tomales Bay. During the summer, Katie and I set out to address whether the west side of Tomales Bay looked similar in terms of genotype. Our specimens were collected off a simple cove located close to White Gulch around the west side peninsula of Tomales Bay. Our specimens were then brought back into the lab, where we performed DNA extraction and successfully determined the genotype of our various samples. I have always had a keen interest in working in a laboratory setting. I don’t know what it is, but something as simple as pressing a plunger on a micropipette and being around fancy expensive machinery excites me. Prior to this program, the only laboratory experience I had, was developed from taking various labs as part of core classes at the SRJC. Although I acquired basic lab skills, working in the Brown Lab this summer allowed me to develop these lab skills to a more advanced level, where I gained confidence in performing procedures and protocols that are likely to be familiar in the future of my career. Katie was also an amazing mentor this summer. Not only was she consistently supportive of my interests and goals, but she also maintained great flexibility in terms of my scheduling. I think at this point, we all get a little bit of anxiety while working with molecular techniques in the lab, but Katie did a great job of making her confidence in me very obvious, which in the end, made me less anxious. This experience at the BML was overall very eye-opening, exposing all of us directly to the scientific community and what’s likely to come next in our academic adventures.

0 Comments

By Quinn AdairQuinton Adair is a third-year biology major at Santa Rosa Junior College (SRJC), intending to transfer to a University of California (UC) in 2024. He is passionate about science and wants to pursue a career in medicine or medical/biological research.  Quinn and mentor Lily taking a crab survey at the BML reserve Quinn and mentor Lily taking a crab survey at the BML reserve As a biology major completing my second semester at Santa Rosa Junior College (SRJC), I had never experienced working in a professional lab setting or engaging in scientific fieldwork. Like many college students, I questioned whether my chosen career path was right for me. Joining this internship was a step towards finding clarity and a deeper understanding of my future. Initially, when I learned about the internship opportunity, conflicting thoughts raced through my mind. On one hand, I recognized that this experience was necessary to reaffirm my academic and personal aspirations. On the other hand, I doubted whether I possessed the necessary knowledge and capabilities to be part of such a program. Looking back now, I can confidently say I belong in the scientific community. During this internship, I had the privilege of being paired with my mentor, Lily McIntire, a fourth-year Marine Ecology Ph.D. student specializing in Thermal Ecology. The experiment I assisted Lily with aimed to explore how thermal quality affects habitat selection and thermoregulatory behaviors in intertidal animals. Throughout the internship, I had the opportunity to assist Lily in various research activities, starting with fieldwork. Together, we ventured to different field sites during low tide to gather data on intertidal organisms. My role involved using various scientific data collection tools, including an infrared camera, a light reader, and a multi-functional environmental meter. Among these tools, I was particularly intrigued and inspired by biomimetic models. Lily handcrafted these models using epoxy, shells, and sponges, creating scientifically accurate tools that showcase the creativity and ingenuity crucial to scientific research. Another aspect of my internship involved Camera Imaging Analysis. During fieldwork, I strategically placed cameras near burrows or crevices with high activity levels. I then analyzed the captured images, tracking movement using Image J software. As I conclude this internship, I am filled with pride for the research I conducted and confidence in the skills I've acquired. Beyond research, I've grown as a student, professional, and self-advocate. Weekly professional development meetings provided invaluable insights into science careers, presenting findings, and advocating for oneself within the scientific community. This experience has granted me a network of peers and mentors, solidifying my path and aspirations within the scientific realm. The journey has been nothing short of transformative, guiding me toward a future where I can contribute to the preservation of our natural world. By Kevin WittI am Kevin Witt, a second-year intern in the SRJC-BML program who has just finished his third year at Santa Rosa Junior College with a series of associate degrees in various scientific disciplines. I will be beginning at Sonoma State in the fall of 2023 as a Junior. I will be studying for a double major in Biochemistry and Geology. After completing my bachelor’s degrees, I hope to pursue a PhD in conservation science, preferably through Davis studying here at BML. This summer I have been helping to prepare an experiment to study the feasibility of using aquaculture to grow gooseneck barnacles. Gooseneck barnacles are filter feeders that live in the rocky intertidal. They grow on a meaty stalk unlike the more widely known volcano style of barnacles. In general, gooseneck barnacles belong to the infraclass Throacia, however for this experiment we are specifically interested in those of the genus Pollicipes. They tend to grow in colonies or groups due to a process known as gregarious aggregation. This means that when a larva is ready to leave the water column and fuse onto a substrate, it generally seeks out an adult of the same species to cement itself onto. It is common for an adult gooseneck barnacle to have many larvae settle onto it. These barnacles are a delicacy in many parts of the world, especially Spain and Portugal. They are the most expensive seafood on the market right now. Their meat can fetch a price of over 100 dollars a pound. Due to the high value of the meat, and the complicated life history of these individuals, they are extremely vulnerable to overharvesting. Traditionally gooseneck barnacles have been collected by free divers, who will harvest multiple entire colonies of them at once. The main problem with this of course is that if an entire colony is harvested, there are no longer any adults left at that location for the larvae to settle on. Since they immensely prefer to land on adults of the same species, this means that most of the larvae do not, in fact, settle at all and die off in the water column. Also, they share a range with many other intertidal mollusks such as muscles. When a colony of barnacles is completely removed it is not uncommon for these other animals to overrun their former locations before new gooseneck barnacles can reestablish a foothold there.

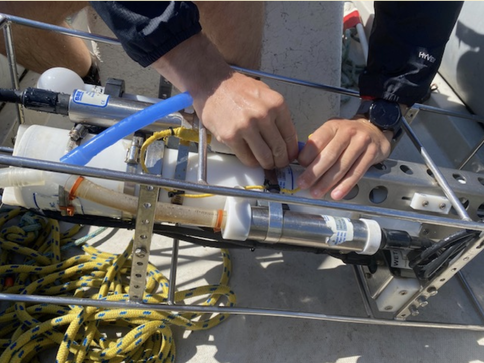

In order to combat this vulnerability, we are looking into the feasibility of growing Pollicipes under controlled conditions. Since they are filter feeders, they need to be grown in moving water. We are using three existing upwellers in the red abalone lab to test three separate high-protein diets, a classic fish food diet using tropical fish flakes, a diet of fly larvae, and a diet tailored to grow shrimp. We are suspending several baskets of barnacles in a column in each upweller. There will be an air stone at the bottom of each column both for aeration and to aid in the uplifting of the food. The experiment will run for six months. We will count the number of individuals in each colony and weigh the colonies at the beginning and end of the experiment as well as measuring the change in size of several marked individuals of each group. We will count the number of dead individuals in each group on a weekly basis. As we are still at the beginning phase of this experiment, we obviously have no data at this point. The results of this experiment will be used to inform future experiments. By Kamryn ConwayI am Kamryn Conway, an SRJC student transferring to UCSD in Fall 2023, majoring in Human Biology. I am interested in systems biology and medicine. My mentor was Keira Monuki, a 4th-year PhD student. The SRJC-BML internship was an eye-opening and rewarding experience. A hope I had before transferring was to learn about research and graduate school, two things I was interested in. BML became the perfect introduction to everything I was curious about. I learned that I want to pursue research, gained a realistic perspective of what that might look like, and had fun participating in fieldwork, field surveys, lab work, and more. During the internship, I started a project involving Acanthinucella spirata, a marine snail, and its egg capsule aggregations. These aggregations are regularly yellow-cream colored but when exposed to environmental stressors, can turn pink, a sign of inviability. Salinity is a known environmental stressor for marine snail egg capsule aggregations, and for this project, we were curious if the temperature is an environmental stressor for A. spirata. This project adds knowledge to the topic of temperature changes and what that could mean for rocky intertidal species range shifts. To gather data, I measured the pink area on 126 egg capsule photos using ImageJ from May and June of 2022 and 2023. I made it a proportion of the total area and ran a statistical analysis. I found that the colder year, 2022, had significantly more pink egg capsules than 2023. I also found a correlation between temperature and the proportion of pink area: cold temperatures and an increase in pink area. Completing this project under Keira’s guidance and being in the BML atmosphere taught me many skills, like improving attention and detail to introducing me to experimental design. I learned that it takes time, and one rarely comes up with perfect, novel ideas but leans on mentors and peers for collaboration. My overall experience at BML was incredible; everyone was kind, welcoming, and always happy to answer questions. I am grateful that this internship strengthened my passion for science and created a desire to pursue research in the future.

By Julian Schiano Di ColaI am in the SRJC-Bodega Marine Lab summer internship studying harmful algal blooms with the Coastal Oceanography Group. I am driven and motivated by my strong work ethic, which makes me feel accomplished when I have accomplished something I thought was difficult. I believe I am great with people when it comes to helping, whether that be having a conversation or being a good listener. My current short term goal is to finish classes at SRJC and gain more experience in research so I can apply to medical school to become a medical doctor. The Coastal Oceanography Group at the Bodega Marine Lab collects data for so many important topics in terms of global warming and overall ocean health. Their data collection varies across many different devices precisely placed in parts of Bodega Bay, the Russian River, and even Fort Bragg. My favorite experience was getting to join Nicholas and Robin on fieldwork by dropping a device that measures temperature and salinity of ocean water in precise locations of the Russian River. We were tasked to collect data of salinity and temperature in precise locations along the river, all varying in depth. It was such a beautiful and sunny day, and doing something active while data collecting out in the real world was the most fun I have had in years. It was something I had no idea the coastal oceanography group got to do, but I felt very thankful that I was invited to do something so interactive. I believe I signed up for the SRJC-Bodega Marine Lab internship to challenge myself. I had never done an internship previously, so I felt that it would be a new experience that I would never forget. I was previously a marine biology major at SRJC back in 2017, but changed my major because I thought it would be too difficult. I am currently interested in pursuing medicine, but I still have interest in something I thought I would not be able to do, even if I think it's too challenging. I believe this internship really opened a new chapter in my life, which I think will allow me to push myself and try internships that are completely different from this one. I do not feel afraid to challenge myself to learn new things anymore.

By Daily AlvarezDaily Alvarez is a 21 year old biology student at the SRJC, intending to transfer to UC Davis and eventually pursue a career in the veterinary field. She is a person passionate about animals, and enjoys spending time out in nature and swimming. This summer has been one of the most incredible summers I have ever experienced. I decided to sign up for this internship with the hopes of getting a glimpse of what the research world has to offer. To my surprise, I got so much more than that. I got to meet great scientists and learn about what they do, I got to learn about white abalones, and most important, I got to do one of my favorite things, spend time with animals.

From working with my mentor, Leela Dixit, I learned about white abalones and what drove them to be endangered. White abalones are threatened by a disease called Withering Syndrome, caused by a bacterium that affects their esophagus and causes them to wither away. This summer I worked with the White Abalone Team with the purpose of helping rebuild their population. I got to assist my mentor in cleaning and swapping the ogo and dulse cultures that we would then feed to the white abalones. I also performed checks twice a day to ensure that the tanks, water flow, air flow, UV treatments, and sumps were working properly. I was able to take part in the heritability experiment where we dissected and took data from abalone populations with the goal of identifying a resistance to the bacterium that causes withering syndrome. Another project I helped with was shipping out white abalone populations that would go to facilities to be monitored and then put back in the ocean. This was truly magnificent to witness. The feeling I got when I heard that I would take part in such an important moment for the white abalone, filled me with joy. There is so much more I could say about the things I got to experience at this internship, this opportunity has allowed me to learn more about life, about the world, about animals, and even more important about people. I feel so grateful to mentor Leela, Lauren, Nora, Audrey and so many more amazing scientists for teaching me about white abalones. In addition, I'm thankful for the Bodega Marine Lab to allow me to experience a summer like this one. This is truly a summer I won't forget! By Bailey GlashanI am a third year student at Santa Rosa Junior College and hope to transfer to UCSC or Cal Poly Humboldt next fall. I am studying Biology with a specific interest in organismal biology, but every time I try something new, I want do that forever, so I like to keep my options open for now. I had a fantastic summer at the Bodega Marine Lab this year, and consider it to be one of the best experiences I could have had. I got to connect with all sorts of people and learn about their role at the lab, and the way that all of their roles fit together to make the lab run. I got to work in the field all summer, and learned a lot about the land we were working on, and I really enjoyed it. Each day, my mentor Luis and I would go out and do weed work to control the encroachment of invasive species on the dunes or coastal prairie, and we would do basic maintenance to make sure that the reserve functions, such as cleaning slippery algae from the greenhouse or fixing the signs in the mudflats. I was also able to complete my own research project at BML this summer. I developed my own proposal, met with the research coordinator, and submitted an application to use the reserve. I did a small survey of the native bees that lived in a small section of coastal prairie above Salmon Creek Beach. On three different days, I collected bees over a forty five minute period, then once they were pinned, I used a key to identify which genus they belonged to. I feel very fortunate to have been able to complete this project and for all of the restoration work that I was able to do on the reserve, but my personal and professional growth over the summer has been the most valuable reward.

By Kordi KokottKordi Kokott is a biology student who recently graduated from the SRJC with an Associates in biology. She’s moving on to become a student at UC Davis to get her bachelor’s in biotechnology. She was an intern at the Bodega Marine Lab in the summer of 2022 and was mentored by Sara Boles. This summer, I actually got to work on two different experiments – one where I helped to set up an experiment, and one where I analyzed data. The first experiment was a nutritional analysis – examining how dulce cultivated at different temperatures would affect the growth and health of two different ages of juvenile abalone. The other experiment I worked on was examining the transgenerational effects of ocean acidification on abalone. For this experiment, I came in as it was almost finished and simply did data analysis.

For the first experiment I helped to set it up, since the actual experiment would run much longer than my stay at the BML. Throughout the time that I spent setting up this experiment I learned a lot about the process behind the science. Making an experiment isn’t necessarily a straightforward process, where you simply have an idea and then execute it. Oftentimes, there are twists and turns along the way. We started out using one container, and then switched to another kind that would work better. We didn’t have the right size of mesh at first, so we had to go out and find some. Our small abalone kept dying, so we had to get a new shipment of them so that it wouldn’t present a confounding factor. All of this happened but still, the experiment went on, because we found ways to solve them. I was able to learn how essential the ability to be flexible and innovative is to science, and that kind of hands-on experience is priceless to a budding scientist. For the second experiment – I had another unique experience: I processed data. Essentially, I examined abalone in photos that had been taken previously and found the area and length of their shell. I didn’t actually do much with this data – my mentor is the one that created figures and the one that did all the real work analyzing it. All I did was draw circles and lines on the screen with a computer mouse. It was boring, tedious, and time consuming - but it was also essential. Examining shell length and size of 495 abalone (yes, I counted) showed me something else about science – it might not always be exciting, but without the somewhat tedious parts, you never can reach any conclusions. Throughout my summer journey at the Bodega Marine Lab, I got to see all sides of science and research. I got to do hands on work, see an experiment get started, and I got to hold an abalone (which was a pretty cool experience). Overall, my time at the BML was in a word, amazing. I feel like I really contributed to something, and my understanding of the scientific process is much broader than it used to be. By Nate BossierNate Bossier is 23 years old, born and raised in Novato California. Recent graduate of Santa Rosa Junior College, Nate is transferring to Cal Poly Humboldt and majoring in Freshwater Fishery Biology. Let me set the scene. It’s 5:30 am in the morning and I’m driving through thick fog blanketing the roads of West Marin. I’m heading to my first fieldwork outing, and thinking “man, I really signed up for this?” This was the beginning of a truly eye opening and fulfilling internship with my mentor and UC Davis PhD student, Priya Shukla. Her study involved investigating heatwave events and their effect on mass die off events caused by Ostreid herpesvirus (OsHV-1) in Pacific Oysters. The study involved comparing two sets of thermally conditioned oysters to try and withstand marine heatwaves and disease events more effectively. My work involved measuring the growth and mortality of those oysters, which were deployed over three different sites in Tomales Bay. This is why fieldwork was so early in the morning; in order to reach the sample bags during low tide. Every other week we would be out there a couple mornings, looking through the oyster bags and counting the amount of dead oysters. We also collected dying and surviving oysters for future analysis. This was my first ever taste of real fieldwork, as compared to labs in my previous biology classes. Getting knee deep and stuck in the bay mud was a blast, and Priya always had different and interesting volunteers coming out to help as well. Getting hands-on experience, as well as being exposed to people at different stages in their academic journey. This honestly reduced my anxiety of fitting into the science community, as for the first time I got to see how scientists are in fact regular people just like me, with a passion for the natural world around them. Priya also got me into the lab side of things. I got to dissect (or shuck, if you prefer) oyster samples collected from the field, in preparation for dehydration and future analysis. I also got lots of experience using ImageJ, a program for measuring small and difficult shapes. Though the less fun side of science, I found the lab work to be quite fulfilling, as well as a nice change of pace from being out in the mud. It showed me I do enjoy both sides of the scientific process.

Overall, I can say this internship has further solidified my goal of going into fisheries biology. Getting hands-on experience in the field and lab, as well as expanding my network and being exposed to so many like minded people is an opportunity I will cherish heading into the next stage of my academic journey. Shout out to Priya for making a truly memorable internship experience! Now off I go to Cal Poly Humboldt! By Zoe RuffattoZoe Ruffatto is a 3rd year SRJC Biology major intending to transfer to a four year university in 2025. She is passionate about learning and wants to pursue a career in some area of biological research. I never imagined myself doing anything in the marine sciences. Despite growing up near the coast, ever since I saw what my younger self referred to as a ‘monster’ in a river on a camping trip, I have been a bit wary of the water. So how did I end up as an intern in a marine laboratory? It was all part of my quest to, in this case literally, ‘test the waters’ in different areas of biological research. I am a third-year SRJC biology major with the dream of a career that allows for lifelong learning. The way I describe my interests to those who ask is that I am ‘a little too interested in a few too many things’. So, the chance to get my first research experience this summer at Bodega Marine Lab absolutely thrilled me, even though it meant that I might end up having to face my fears a bit. I spent my summer getting experience in both field and lab work with my mentor Lily McIntire and got to design my very first research project with Lily’s help. My project aimed to begin looking at the reason that crabs blow bubbles when they are removed from the water. Since Lily’s work involves temperature, I was interested to see if they blew bubbles when they got too hot to help them evaporatively cool, which is one of the possible explanations for this phenomenon. Coached by Lily, I designed an experiment with five temperature treatments, each with five grumpy, pinchy participants. The crabs were all held at roughly 100% humidity to reduce the chance that they were blowing bubbles to aerate their gills. I recorded their temperature and whether they were bubbling at 10-minute intervals 7 times for each of five temperature treatments. Lily and I found that although the temperature treatments were statistically different from each other, meaning that variation in bubbling between trials would be due to temperature, not random chance, there was no statistically significant difference in bubbling frequency between treatments. Although these results might seem like a failure, they truly were not. Lily reminded me throughout the experiment, that “no results are still results”. And by the end of the experiment, I really did believe her. Getting to create an experiment and having my own data to analyze helped me see all the ways that my results would be useful in the future. Because of my pilot study, when Lily wants to control bubbling in her future experiments, she would now know that at higher humidity, crabs don't tend to bubble even when heated. Not only did I get my first lab research experience this summer, but I also got to see first-hand what field research looks like. And no, I did not end up having to face any fears, nor did I see any new ‘monsters’. I felt surprisingly comfortable out in the intertidal with Lily by my side. Before this internship, when I thought of research, I thought of lab work. In my head, research involved sterile environments, Petri dishes, running experiments, and cell cultures; things that involved manipulating something and watching the response. I did not realize the extent to which simply observing and recording data about one’s study species in the field is an integral part of research. When out in the field with Lily, we would start the day with ‘crab walks’ where we would traverse a section of her field site and record the temperatures and habitats of the crabs we saw. We never tried to catch the crabs, we just noted where they were and took an average temperature. The goal was to interact with them as little as possible. Although we were collecting data, it wasn't in the way I had always thought data was gathered: in a lab setting. It was very valuable for me to see how, especially early in a research project, you often do very little to manipulate what you are studying and still end up with important data.

Overall, I think had a very unique internship experience, because not only was I just beginning my research journey, but my mentor was also at an early stage in her project. This meant that I got to see the steps that need to be taken to start a research project and was able to gain an appreciation for how much effort goes into organizing and planning a project. Considering that I see myself in a career that involves research and have an immense passion for learning, this was the perfect introduction to my future. I am leaving this summer experience with my first piece of research under my belt and a fabulous support network of scientists at Bodega Marine Lab. Who knows, maybe I will end up in the marine sciences after all! |

AuthorsBML-SRJC Interns! Archives

April 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed